“I could see the pilot's face as he closed on us,” Currah said. “My tracers went right into the cockpit window and I saw him slip behind the console just before he hit us.”

A Shoshoni Kid at Okinawa - Bud Currah – Kamikaze Strike April 22, 1945

by Randy Tucker

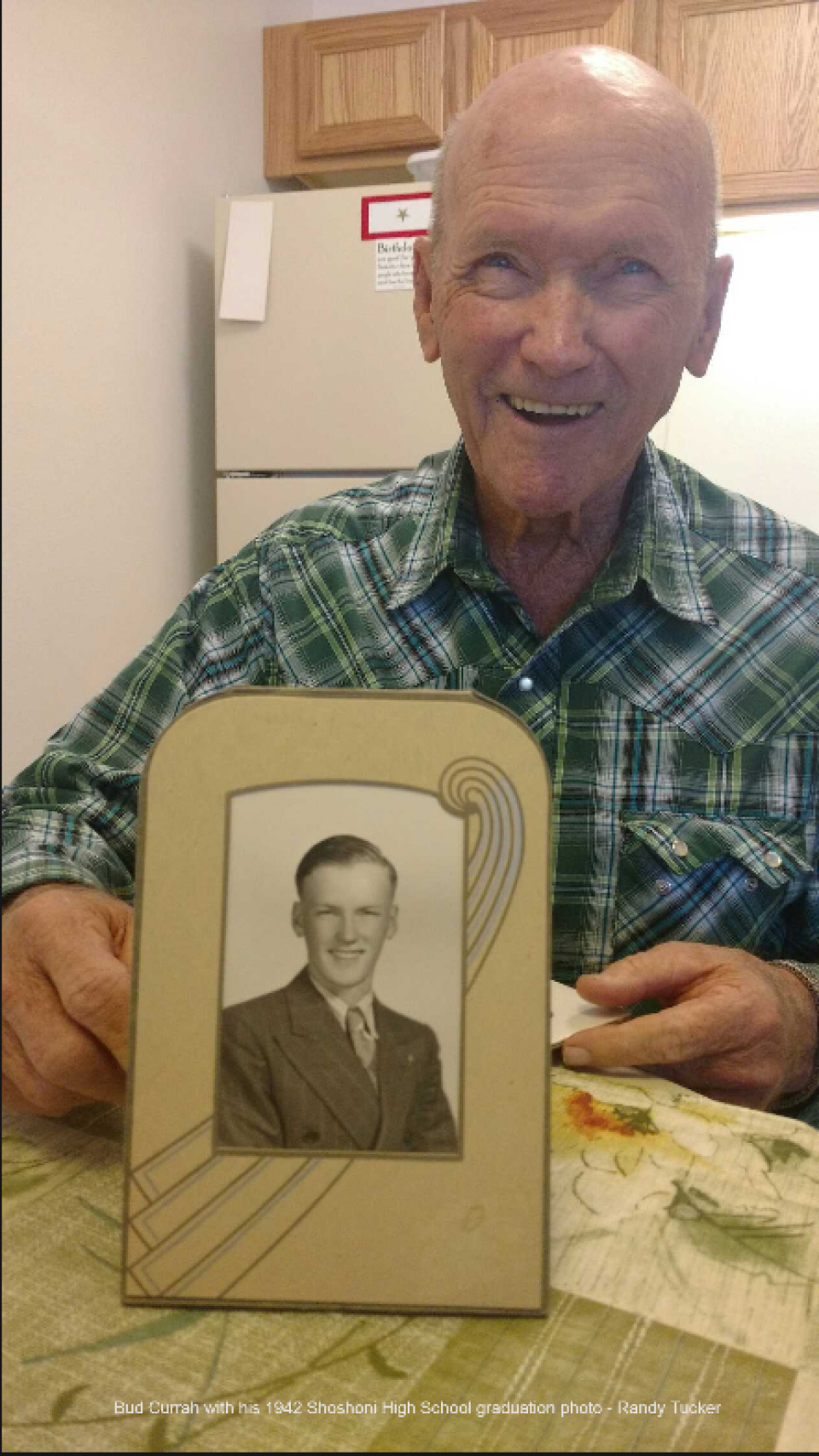

He was throwing a football with his friend Dale Downey on a cold December day when the word came across the radio. His dad came outside telling them that the Japanese had just bombed Pearl Harbor.

Thomas “Bud” Currah and his friend Dale in youthful ignorance quickly replied, “Don’t worry; we’ll take care of it. Dad wasn’t too happy” Currah said.

Currah’s father, Hugh, an infantryman in the Great War just gave the boys a knowing nod and went back inside.

After an eight-year hiatus, the Wranglers fielded a 6-man team in the fall of 1941. Bud and Paul were integral parts of coach Carl Dir’s team that won their first five games before falling 38-14 to Cowley in the Big Horn Basin Championship game on November 19.

Three weeks later their carefree days as farm boys and high school football players were about to come to an end.

Downey was the sportswriter for the Wrangler student newspaper and often told Currah that he was getting tired of writing “Downey to Currah” in every football story.

Enlistment and Training

The two enlisted in the U.S. Navy on the buddy plan and took basic training together before different orders changed their military paths.

After basic training Currah was sent to Farragut, Idaho for Navy boat training on Lake Pend Oreille. After five months in Idaho, he transferred to Ames, Iowa, and a diesel mechanic school at Iowa State University. Downey was assigned to naval air traffic control school.

“There was a cook school at Iowa State taught by farm women,” Currah said. “We ate real well.”

Currah’s final training came in amphibious assault tactics at Solomon Peninsula on Chesapeake Bay. “My specialty was the variable pitch propeller driven by four straight eight diesel engines on each of the two shafts,” Currah said.

He was assigned to one of the smallest ocean-going craft in the U.S Navy’s entire Pacific fleet.

The USS LCS(L) 15, was commissioned and launched into Boston Harbor. Currah arrived with the rest of his crew before they did a shake-down cruise to Norfolk, Virginia. They crossed through the Panama Canal, and then up the coast to San Diego before heading off to war in the Pacific.

The LCS(L) was constructed in three different shipyards. Two were in Portland, Oregon, Commercial Iron Works, and the Albina Engine and Machine Works.

George Lawley and Sons built them in Neponset, Massachusetts. They were the original builders of the first LCS(L) ship.

The LCS(L) first saw action on D-Day on June 6, 1944. Their use in Europe came to an end once the allies successfully landed. The future of this small craft lay half-a-world away, in the Pacific.

The LCS(L) 15 was launched on September 26, 1944. Empty it weighed only 250 tons and fully loaded with men and equipment it tipped the scales at 387 tons.

Small, but heavily armed it was to become a workhorse for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps in the Philippines, Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Traversing the vast Pacific Ocean in a craft with a flat bottom, designed to provide close range fire support to Marines in just a few inches of water was a challenge, especially to a kid from Wyoming who had never seen water larger than a mountain lake. Bud never learned to swim.

The LCS(L) 15 carried one three-inch gun, a pair of twin 40mm anti-aircraft guns, four 20mm anti-aircraft guns, rocket launchers and was sprinkled with 50 caliber machine guns. Once they joined Admiral Raymond Spruance at the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet in the Philippines they had 4.2-inch mortars added to their armament.

Bud was a Motorman Second Class, a mechanic on a ship powered by eight Gray Marine diesel engines. They powered twin propellers that when opened wide could sail the ship at 16.5 knots. Cruising speed was just 12 knots. These weren’t PT boats, destroyers or fast attack cruisers. Their job was to move in close to short or to serve as pickets against the growing threat of Kamikazes as the United States advanced closer to the Japanese home islands.

There were 130 total LCS(L) ships in the Pacific. These ships were never named, just identified by their number and the designation of either (S) for small, or (L) for large. They were beefed up versions of the LCI (Land Craft Infantry) used to land men and materiel at places like Omaha, Utah, Sword and Juno Beaches on D-Day, the Canadians and English used a handful of the first LCS (L)s at D-Day.

They saw action in Borneo, the Philippines, Iwo Jima and in the final land battle of the Second World War, Okinawa.

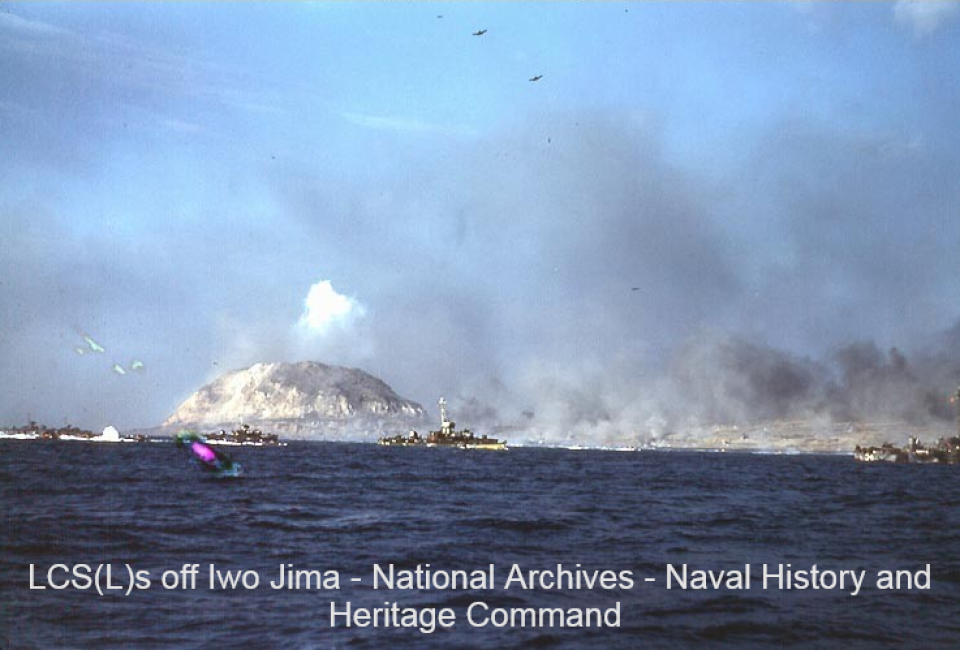

Iwo Jima

Bud’s ship didn’t arrive in time for the Borneo or Philippines campaign, but they were in the thick of it on the black sands of Iwo Jima and the war ended for the 65 men on board the LCS(L) 15 during the invasion of Okinawa.

On February 19, 1945. Thomas Wayland Currah went to war for the first time. In the pre-dawn hours a few miles off the black sand of Iwo Jima, Bud and the other 64 men of the LCS(L) 15 waited for the final 76-minute barrage of heavy guns from American cruisers and battleships and the bombing by hundreds of planes off nearby aircraft carriers to end.

No one on board got much sleep the previous three days before the invasion began as the naval and air bombardment of the tiny island went on non-stop for 72 hours.

The LCS(L) 15 was part of the close support portion of the landing. Lines of smaller attack ships and landing craft were spaced between destroyers and cruisers a few thousand yards offshore. Nine LCIs adapted to fire 5-inch rockets, 18 LCI(M)s (Landing Craft Infantry Mechanized) filled with Marines, 12 LCI(G)s (Landing Craft Infantry Gunboats, smaller versions of the LCS(L)) and a dozen LCS(L)s moved toward the shore.

Bud manned a .50 caliber machine gun as the LCS(L) 15 moved slowly closer to the island. Inside 1000 yards of the beach, they began to take Japanese machine gun fire and spouts of water from Japanese mortars sprayed the crewmen manning the 20mm, 40mm, .50 caliber and three-inch guns.

The LCS(L)s operated in two groups of six, coordinating with the other small craft to provide fire support into the jungle surrounding the beaches as the Marines stormed ashore.

Bud fired his .50 Cal into ravines and at Japanese troops on shore. The LCS(L)s and the nine LCIs opened fire with 4.5 and 5-inch rockets in coordinated attacks ordered by the Marines on shore.

The smaller craft set their bows on the sand. The LCS(L)s moved until the bow touched the bottom then held position so they weren’t beached.

The LCS(L)s were initially under the control of a shore fire control party but as the battle ensued and the Marine officers realized how effective they were, they let them operate more independently.

This was an intricate orchestra of destruction. The gunboats fired their rockets 90 and 45 minutes before the Marines hit the beach, reloaded then fired again 10 minutes before the first American boot hit the sand.

They fired a final rocket barrage 300 to 500 yards inland as the landing craft neared the sand. They had to quit the barrage since carrier-based aircraft began strafing the beach as the Marines came ashore.

Battle plans usually fall apart with the first bullet fired, but the four gunboat units, 15 LCS(L)s and LCI(G)s were to move in single file around the battleships and cruisers, between the destroyers and lead the landing craft off the Marine troop ships before spreading out to fire close range support. The LCS(L)s were able to carry out their mission flawlessly, but the LCI(G)s were decimated, with only three serviceable for the invasion. Now 15 gunboats had to do the job originally designed for 24.

In position, the LCS(L)s began firing their 40mm guns towards the slopes of imposing Mount Suribachi in close support of the Marines moving inland.

The newly mounted mortars began firing in response to Marine grid coordinates. They battle group of 15 small ships delivered over 17,000 rounds of 4.2-inch mortars on enemy positions before the battle was over. They fired 9,500 rockets as well.

Heavy cruisers kept the smaller ships supplied with ammunition, rockets and mortar shells.

At night with only occasional requests for fire support, the 15 gunboats searched for Japanese submarines trying to either get in position to attack the capital ships or to extricate high ranking officers from Iwo Jima.

Bud and his 64 shipmates remained on duty just offshore at Iwo Jima until the end of March. He watched as Marines raised the flag at the top of Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945. One of the most iconic moments in Marine Corps history.

Their job complete on the little rock outcropping in the middle of the vastness of the North Pacific complete. They set course for Okinawa 600 miles to the northwest of Iwo Jima.

The approximate totals of ordinance fired by the gunboats was astronomical. An approximate 60,000 4.2-inch mortar rounds, 8,000 4.5-inch BR rockets, 9,500 5-inch SSR rockets and 116,000 rounds of 40mm ammunition.

The invasion of Okinawa followed the same battle plan as Iwo Jima two months earlier.

Okinawa

Sleep deprivation was even worse with a heavier concentration of cruisers and battleships and 31 fleet, light and escort carriers. The skies were filled with aircraft in sunlight and even after dark. In one six-hour period, the capital ships fired an incredible 30,000 shells into Sugarloaf Mountain.

The LCS(L)s moved in close during the initial invasion but found few targets. The Japanese had changed tactics, allowing the Marines to land and digging in behind heavily fortified positions further inland.

The LCS(L) 15 had another, much more dangerous mission about to unfold.

From April 1 to June 22, 1945, American sailors faced the most devastating threat of the Pacific War, the kamikaze pilots of Japan’s Imperial Special Attack Corps.

What began as a desperate gamble by Japan soon became the deadliest naval engagement in U.S. history. Wave after wave of suicide aircraft attacked the invasion fleet, testing the courage and endurance of every sailor. Japanese leaders hoped that such sacrifice might delay defeat and force a negotiated peace. It wasn’t in the American game plan. The U.S. Navy improvised new tactics.

For the first time in the war, American naval losses exceeded those of the soldiers and Marines fighting ashore. The Navy established a ring of radar picket stations around the island to provide early warning of approaching Japanese aircraft, in particular kamikaze formations. These stations extended far beyond the main invasion fleet, forming a defensive perimeter at sea.

Each picket station was manned by destroyers and smaller support vessels, including a dozen LCS(L)s. Their job was to detect and engage incoming aircraft using radar, report bearing and altitude to the fighter direction centers.

LCS(L) 15 was at Radar Picket Station 14, located southwest of Okinawa, its coordinates defined by range and bearing from Point Bolo, a fixed reference position on the island’s southern coast. This station was part of the western segment of the radar screen and was among the first to encounter kamikaze attacks approaching from Formosa and the East China Sea.

Duty on the radar picket line was among the most hazardous in the Pacific war. Ships stationed there operated great distances from the main fleet, with minimal air cover. Kamikaze pilots, aware of their strategic importance, focused their attacks on these isolated picket ships.

Despite the high risk, the radar picket network around Okinawa was indispensable. Early detection and interception saved countless ships closer to the island and provided critical minutes of warning for fleet defense and air coordination throughout the operation.

Kamikaze

Bud was a mechanic but had a battle station firing a .50 Cal machine gun near the 10 MK 7 rocket launchers in the middle of the ship.

“We had 13 calls to general quarters that day,” Currah recalled. “I had just taken a shower when the alarm went off again.”

After fighting in the opening days of the invasion of Okinawa beginning on Easter Sunday three weeks before, the LCS-15 was now on picket duty in the farthest line of 14 stations from Okinawa. LCS(L)s, destroyers, and minesweepers were arranged in a five-mile diameter circle and protected by Marine pilots flying air cover. Their assignment was to intercept Kamikazes trying to reach the American battleships and large aircraft carriers closer to Okinawa.

“Radar picked up 21 Japanese planes heading towards us,” Currah said.

Four Marine S4U Corsairs provided air cover for the group of ships and the Marine pilots were able to shoot down 20 of the 21 Kamikazes before they reached the ships at point 14.

“We could hear the pilots on the radio. Splash one bogey they’d say and we’d all hurrah, hurrah,” Currah recalled.

One plane made it through the Marines, a Val bomber. Firing his .50 Cal along with other sailors pouring fire from a twin 40mm battery someone hit the Val and it began to smoke.

“He wanted to take out a destroyer but when he started to smoke he turned on us,” Currah said. The bomber turned and began to dive towards the LCS(L) 15.

“I could see the pilot's face as he closed on us,” Currah said. “My tracers went right into the cockpit window and I saw him slip behind the console just before he hit us.”

Currah’s ammunition handler panicked as the Val closed in and ran forward from their position.

“He had headphones on and ran a few yards but the line to the phones caught him, knocked him backward off his feet, and knocked him out,” Currah said. “It saved his life.”

The bomber flew through the center of the ship and out the other side of the hull. The blast threw Currah against a bulkhead, breaking four of his ribs but he didn’t realize it until two days later when he had trouble breathing. “Adrenaline is a powerful thing, you just don’t notice you’re hurt,” he said. “I watched an engine and a tire go flying by. He didn’t last very long but he hit the ship right where he wanted to. It lifted the ship right out of the water.”

The shallow draft LCS began to sink rapidly. In three-and-a-half minutes the ship was below the waves.

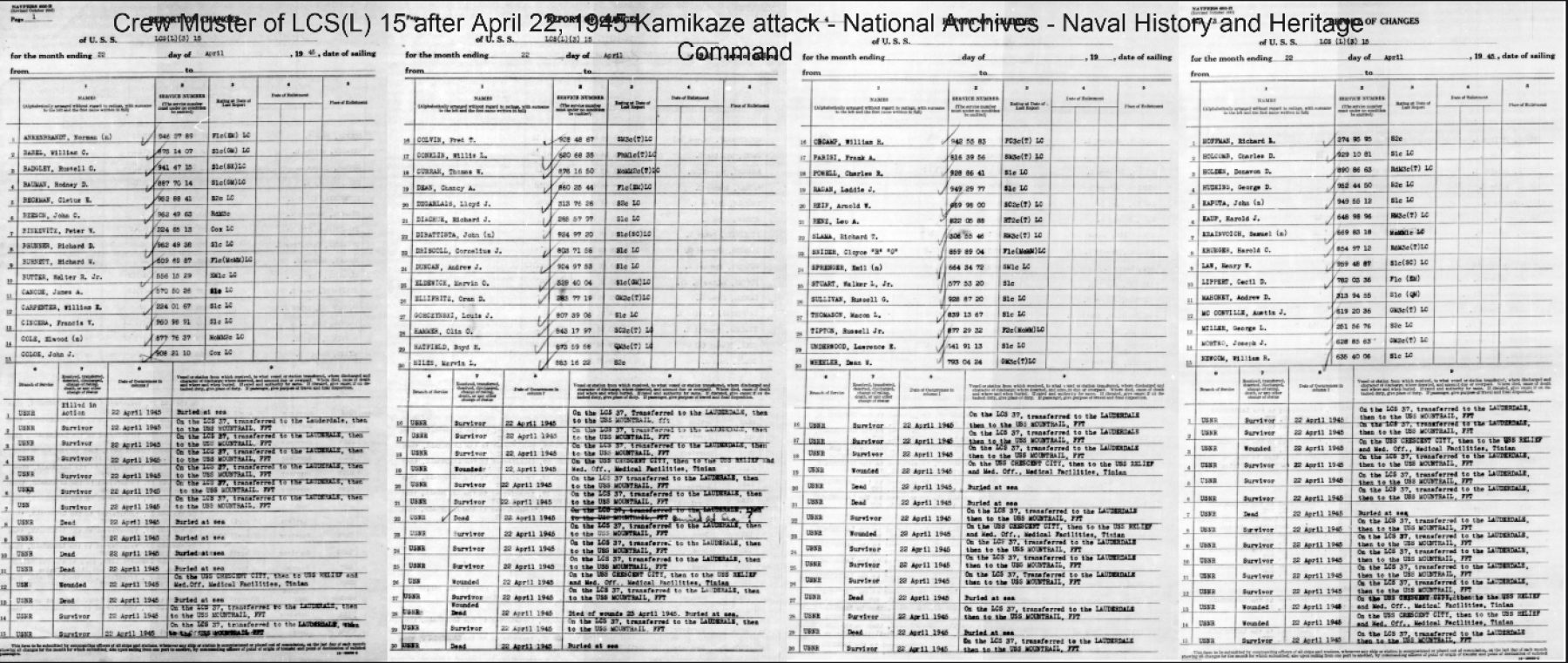

14 sailors were killed instantly in the attack, and more were injured including many with severe burns.

Currah was a non-swimmer in the middle of an ocean over a mile deep. He scrambled for a Mae West life preserver and pulled the waist strap tight but didn’t adjust the vest properly.

“I hit the water and the vest popped up, forcing my head back,” Currah said. “Another sailor saw what was happening and tried to pull me up. We spotted an empty 30-gallon GI can floating nearby, I grabbed one handle and he got the other. I told him if we see a shark I’m getting inside the can.”

Currah was in the water 45 minutes to an hour before the USS William D. Porter (DD 579) a destroyer, fished him out of the sea. Most of the crew was rescued by their sister ship the LCS(L) 37. Other neighboring ships picked up the rest of the 55 survivors. Another man was killed later by a shark in addition to the 14 in the Kamikaze attack.

“An officer on the destroyer told the men to find someone my size and get me some dry clothes,” Currah said. His water-soaked clothes were full of diesel fuel and oil from the attack.

“You spend so much time with these guys on a small ship that you get to know everybody really well. It was like losing 15 brothers,” Currah said. “An engine room sailor from Butte, Montana crawled out of the hole made by the bomber and dropped into the water. I saw him a few days later he was bandaged from head to toe with severe burns.”

The survivors were assembled on an APA, (Amphibious Transport) along with the victims of the attack.

“We had a burial at sea,” Currah said. “Taps bring everything back. If they play taps at a military funeral I get lost.”

Bud’s fallen shipmates:

- Ankenbrandt, Norman J. — F1, SN 9492789

- Brunner, Richard D. — SEA1, SN 9624938

- Burnett, Richard W. — F1, SN 6096987

- Butter, Walter R., Jr. — EM1, SN 5561529

- Canode, James A. — SEA1, SN 5705026

- Cincera, Francis V. — SEA1, SN 9609891

- Conklin, Willis L. — PHM1, SN 6206835

- Dibattista, John — SEA1, SN 9429720

- Hammer, Olin O. — SC2, SN 8431797 — believed died of wounds (23 Apr 1945)

- Hiles, Marvin L. — SEA2, SN 8831622

- Kreinovich, Samuel — MOMM1, SN 6698318

- Reif, Arnold W. — SC2, SN 6699800

- Renz, Leo A. — RT2, SN 8220588

- Thomason, Macon L. — SEA1, SN 8391367

- Underwood, Lawrence E., Jr. — SEA1, SN 6419113

Here is the official Navy Summary of the sinking of the LCS(L) 15

Sunk: 22 April 1945, off Okinawa (Radar Picket Station No. 14).

Cause: Kamikaze (Aichi D3A “Val”) struck LCS(L)-15, bombs detonated; the ship listed and sank within minutes.

Time of sinking (reported): The ship was abandoned about 1832 and sank about 1834 (22 Apr 1945).

Casualties reported: 15 killed, 11 wounded (survivors picked up by nearby ships).

Context: LCS(L)-15 was on radar-picket/anti-air duty with destroyers and other LCS(L) craft when the attack occurred during the intense kamikaze assaults on the Okinawa picket line.

Currah moved from the William D. Porter that rescued him, to the APA and eventually the USS Intrepid, an aircraft carrier. Ironically, the William D. Porter was sunk in a kamikaze attack in June and the entire crew was rescued by three LCS(L) ships.

The crew of the LCS(L) 15 along with the crews of the other 129 small ships that operated at Iwo Jima and Okinawa were manned by very young men, most teenagers or men in their early 20s.

The LCS(L) 15 commander, the “Old Man” was Lieutenant Junior Grade Ned Harold Bower from Ohio, he was only 24 years old. The other officers Hilrey Leon Aven, Bernard Joseph Hachenson, Orville Paul Sanders, Carl Washington Schlegel and Luther B. Stover were all ensigns. The were no petty officers on board, the highest-ranking enlisted men were seaman first class.

Moving to Civilian Life

Currah and the other surviving members of the LCS(L) 15 were taken to San Francisco on the Intrepid along with 1500 sailors rescued from the USS Franklin, an aircraft carrier badly damaged in March.

“We pulled into San Francisco in June 1945,” Currah said.

Orders were cut to reassign the men after their leave was up.

“Pretty near all my buddies went back but they found out I’d been a parts man at the Shoshoni Garage and I was assigned to a parts depot in San Diego,” Currah said.

Currah was discharged in 1946, just after Christmas.

“They offered me petty officer rank if I re-enlisted but I already had two kids and wanted to get home,” Currah said.

Currah’s wife Marge and her twin sister Maggie were also from Shoshoni and worked as riveters in a San Diego plant during the war.

The couple met near the family farm after Marge’s family moved to the valley near Shoshoni.

“One day two girls rode past the farm on a horse,” Currah said. “They were twins and pretty cute.” The sisters later moved to southern California to work in the war effort.

The couple was married on a whirlwind seven-day trip to Shoshoni on December 19, 1944, after the LCS(L) 15 docked in San Francisco.

“The captain wanted to marry us but I wasn’t 21 so he couldn’t do it,” Currah said. “Marge only had to be 18. The skipper gave me seven days of leave. We caught a bus for Shoshoni, made it to Rawlins and there was Mr. Spaulding the Shoshoni High School principal sitting in the lobby of a hotel. He gave us a ride to Shoshoni.”

The couple was married in the little log church in Missouri Valley that still sits along the highway to Pavillion.

They had six sons.

He entered the construction business and had a long career in Casper. He was an active with the American Legion baseball program, and a licensed Wyoming outfitter. Bud and Marge retired to Star Valley Ranch, but he returned home to Shoshoni, where he served several terms as mayor. In his final years Bud was active in the Hunting with Heroes Program that takes disabled veterans on big game hunts in Central Wyoming.

Bud had a vibrant personality, warm, friendly and with just a glint of mischief in his eyes. He was a classic story teller.

Bud Currah remained a familiar sight around Shoshoni High School sporting events and was honored as a team captain in the Wranglers 2012 homecoming game.

Currah passed away on January 15, 2021, at 96 years of age.